I do this all the time! I tell myself I need to take a blog break to work on other stuff like not being unemployed and homeless but then I research one topic… which makes me curious about another… which leads to one crazy, super long post and then a solid month of radio silence!

Sorry about that ;)

What if Mindy Kaling did a show about microbes?

So my passion du jour is gut microbiome research and The Mindy Project starring Mindy Kaling. (For the sake of the blog, we should probably focus on the gut microbiome part – but, seriously: That show deserves more credit!!)

Ok, so last post we found out that gut bacteria (or “microbes”) from obese mice can actually induce neurocognitive issues in healthy mice (like anxiety symptoms, memory problems and repetitive behaviors) – which is kinda impressive, since it proves that diet-related changes to the gut microbiome are important enough to alter brain function even in the absence of obesity.

Translation?

Bacteria has a lot to do with your brain. The scale? Not so much.

Gut microbiome déjà vu

If you’re a regular reader, these next few sections might sound pretty familiar (feel free to scroll through to the new ADHD stuff – but I did add some new facts/studies!). For everyone else, I just wanted to take a quick second to recap what we know so far about the link between stomach problems and psychological disturbance. (I don’t know why that sounded so boring? But it’s super interesting, I promise!)

For instance, did you know people with irritable bowel syndrome experience 3 times the rate of depression compared to the general population?

I know, crazy right?!

A brief refresher course on the gut microbiome

- Our bodies are home to nearly 100 trillion bacteria, including over 1,000 different species – whose collective genome contains at least 100 times as many genes as our own.

- A “microbiome” or “microbiota” is a little bacteria universe (i.e., our “gut microbiome” refers to the bacteria in our gut).

- We’ve known for a while that our brain talks to our gut (known as “top-down” communication – think: getting an upset stomach when you’re nervous), but we’ve just recently realized that our little gut bacteria friends can actually communicate with our brain (“bottom-up” talk).

*Time out: If you haven’t read the Justin Timberlake/gut microbiome post, I highly recommend pushing pause and heading over there first. It has a ton of details that will help this whole thing make a lot more sense!

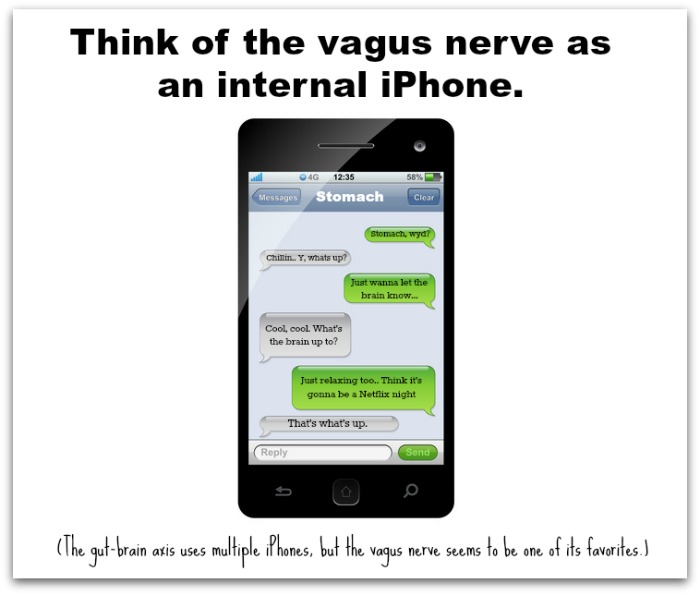

Long story short, though: If you trust those crazy kids over at Molecular and Cellular Life Sciences (and I’m gonna go out on a limb and say we should) – it seems like our stomach communicates with our brain through multiple pathways, the two main ones being: 1) the vagus nerve and 2) hormonal signaling.

The details aren’t super important for today’s post, but just think of the vagus nerve route as a neural pathway – like a bunch of info getting relayed up a big tree that branches out into the central nervous system – while the hormonal route kinda cuts out the middle man: Your stomach releases gut peptides which act directly on the brain and stimulate activity without having to climb up the vagus nerve tree. There’s other means of communication (and that’s the exciting part: researchers are just now beginning to discover them!) but these two seem to be the all-stars.

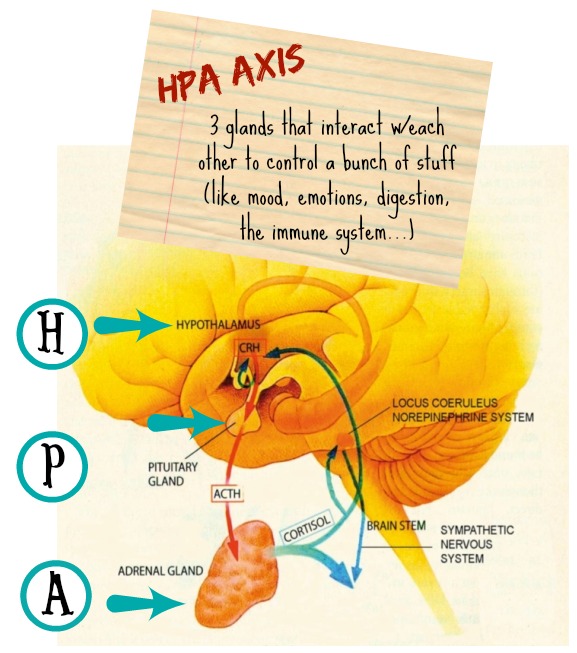

Ok, so when it comes to gut-brain/behavior stuff, most text convos pathways usually lead to some kind of impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis – which is super important to this whole equation:

For example, stressful situations can trigger the HPA axis to alter gastrointestinal motility, secretions and blood flow (top-down talk) – which then gets communicated back to the brain and can result in feelings of nausea and pain. Likewise, researchers have found that altering the gut microbiota of mice can influence HPA activity (bottom-up talk), leading to exaggerated responses to stress.

What’s Ben Affleck gluten got to do with it?

Again, I feel bad referring you guys back to old posts – but if you haven’t read Gluten and Depression: The Jimi Hendrix Experience, now would be the perfect time! We’ll rehash the basics below (no pun intended haha #hash), but the original post has a ton more info!

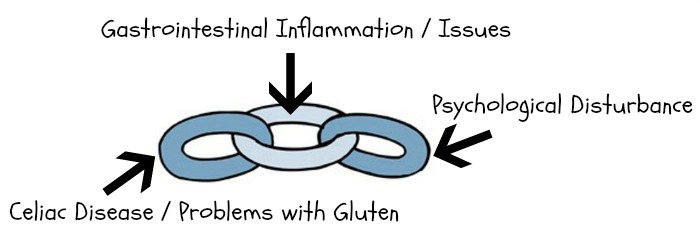

Ok, so gastrointestinal (GI) distress has long been linked to psychological disturbance – and gluten allergies/celiac disease can cause some SERIOUS gastrointestinal problems. That’s why we’re talking so much about the gut microbiome!

For example, a 1998 study of 92 celiac disease patients found that approximately one-third suffer from depression. This particular connection – between celiac disease and depression – is popularly attributed to a damaged/reduced intestinal surface which prevents patients from absorbing critical nutrients needed to manufacture neurotransmitters like serotonin. (I think we all know how I feel about the serotonin hypothesis by this point, but flash back to our #HowDoYouKnow post for a more in-depth discussion!)

However, newer studies (1, 2) are showing that in experiments resulting in increased GI inflammation, there are notable increases in anxiety-like behavior – and treatment with a probiotic (i.e., good bacteria) calms things down – which points the finger at the gut microbiome.

While research is still in a super early stage, there’s a lot of talk about the vagus nerve, altered protein levels, BDNF (a neurotrophic growth factor that’s basically like Miracle Grow for your brain) and a bunch of other non-serotonin-exclusive stuff :) As the researchers over at Gastroenterology put it, “Our results indicate that during chronic gut inflammation, the mechanisms involved in signaling to the brain are complex.”

(Emphasis added is my own – because after reading all of these studies, I feel like “complex” is the understatement of the year!!)

No matter what way you look at it, though, taking gluten out of the equation seems to make things a lot better…

Anxiety and gluten

Oh! This is one of my favorites!

A 2001 study published by the Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology looked at 35 celiac diseases patients before and after one year of following a gluten-free diet (GFD). The celiac group was compared to a control group of healthy subjects matched for gender, age and socio-economic status.

Prior to the GFD, the celiac group showed much higher levels of state anxiety than the controls (71.4% versus 23.7%) and significantly higher levels of depression (57.1% versus 9.6%). After one year of following a GFD, the percentage of state anxiety in the celiac group dropped 45.7% – plummeting from 71.4% to 25.7%!

Even non-celiac patients seem to be affected by the phenomena: Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics published a really cool study last year finding that among 22 subjects with irritable bowel syndrome who did not have celiac disease, “short-term exposure to gluten specifically induced current feelings of depression.”

So, like, obviously something’s up with all this gluten stuff. And it’s apparently not limited to mood and anxiety disorders…

ADHD and gluten

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) show a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development. (For a full list of diagnostic criteria, head on over to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

*Sidebar for all my fellow science nerds: While there’s a ton of controversy over causes, diagnosis and treatment, you’re probably aware that ADHD pathophysiology models that focus on neurotransmitter problems usually zero in on dopamine and norepinephrine/ noradrenaline. (Cheat sheet for my non-nerd friends: Serotonin is associated with mood and emotional regulation. Norepinephrine works to focus attention. Dopamine is all about rewards processing.) For the purpose of today’s post, we’re gonna keep everything pretty simple – but if you wanna dig into all the neurochemistry stuff, check out this 2011 page-turner: The Roles of Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.

Just keep in mind, as the study authors point out: “The precise neurobiological mechanisms underlying [ADHD] and its treatment are poorly understood.” (And if you’re realllly into neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome, consider following up with Gut Feelings: The Emerging Biology of Gut-Brain Communication! #partytime)

Alright, so most of my gut microbiome research to-date has focused on depression and the HPA axis stuff discussed above – and I’ll be straight up: There’s a lot of complex interplay involving gut bacteria and direct neural pathways that I’m still trying to wrap my mind around (a lot of: what came first, the chicken or the egg? kind of confusion… right now I’m just like, “The vagus nerve is important, the end!”) – but as I learn more, I’ll post more #justkeepinitreal :)

It’s hard because gut microbiome research in this area is so new and I spend so much time watching The Mindy Project on Hulu but here’s some of the big ADHD stuff that caught my eye:

- Like I said, most ADHD neurotransmitter talk centers around elevated levels of dopamine. But recently Dr. James Greenblatt, a clinical faculty member at Tufts Medical School, introduced a cool, gut microbiome twist to the conversation: The metabolite HPHPA (a chemical byproduct of a particular type of bacteria called clostridia) causes deactivation of an enzyme that normally helps dopamine convert into neuroepinephrine – which causes a build-up of dopamine. (And remember: Elevated levels of dopamine are thought to be involved with ADHD.) In this 2013 interview, Greenblatt talks about how probiotics (aimed at decreasing abnormally high HPHPA levels) help his patients’ ADHD symptoms decrease and, in some cases, completely disappear. (Worth noting: Greenblatt says, “Eight out of 10 people’s [HPHPA levels] are fine. But in the two patients where it’s elevated, it can have profound effects on the nervous system.”) Definitely worth the read if you have extra time!

PS. I know that info didn’t have anything to do with gluten, but I was on such a bacteria-study-high I couldn’t help but include it! :)

- Ok, so the big thing I really wanted to share today was this 2011 study that found that celiac disease is “markedly overrepresented” among ADHD patients. Researchers also noted that after following a gluten-free diet for a least six months, celiac disease patients with ADHD (or their parents) reported “a significant improvement” in behavior and functioning – leading researchers to “strongly suggest” that celiac disease be included in the ADHD symptom checklist!

Ok, time to switch gears just a little bit…

Autism and gluten

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) demonstrate persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts. (For a full list of diagnostic criteria, head on over to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Estimates suggest upwards of 90% of children with ASD experience some type of feeding related concern. Yep, you read that right: NINETY PERCENT!! And get this, research (1 & 2 as cited by 3) has shown that:

Food selectivity (i.e., only eating a narrow variety of foods by type, texture, and/or presentation) represents the most pervasive feeding issue associated with ASD, typically in the form of strong preferences for starches, snack and processed foods while rejecting most (if not all) fruits, vegetables, and/or proteins.

And starches, snack and processed foods usually have a ton of gluten – which is interesting since, as you’ll read in a second, introducing a gluten-free diet often improves autism symptoms!

(Before you ask, researchers have written as recently as 2013 that: “Available theories do not explain the pattern of dietary preference observed in ASD, including why this population gravitates toward consuming fats, snacks, and other processed foods while avoiding vegetables and fruits.”)

BTW: I found this quote in Nutritional Neuroscience that I thought really summed up the difficulties I was having in decoding this particular topic – as well as my motivation in seeking out gut microbiome/gluten research:

The continued lack of a universally pertinent theory of etiology and pathology combined with an absence of consistent genetic or biological correlates continues to constrain knowledge of the condition. There is an increasing recognition that the expression of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in some sub-groups may also include a number of additional elements beyond psychiatry that may be potentially relevant.

I feel like that’s what this post – and basically the whole blog! – is all about: Seeking out elements beyond psychiatry that may be potentially relevant :) So here’s hoping these next few points fit the bill!

- The Journal of Child Neurology published a fascinating case study of a 5-year-old boy diagnosed with severe autism who was prescribed a gluten-free diet. As the researchers note, “Within one month, the boy’s gastrointestinal symptoms were relieved and his behavior had changed dramatically. Within three months, his functioning had improved so much that he no longer required an individualized learning program and was able to enter a normal classroom with no aide.”

- A 2010 study found that introducing a gluten-free diet had a “significant beneficial group effect at 8, 12 and 24 months” on core autistic and related behaviors of pre-pubescent children diagnosed with ASD.

- Going back to the HPHPA thing, another 2010 study found that HPHPA levels are much higher in the urine of autistic children and that treatment aimed at fighting the bacteria clostridia results in decreased symptom presentation. (Again: Not a gluten thing, but too interesting not to include!) And speaking of bacteria stuff, if you have a second, check out: The Gut Microbiome: A New Frontier in Autism Research – sooo good!

Ok, I’m exhausted!

I seriously need to get better at pacing myself, because I realize most of my posts follow the same crazy pattern: Fun, light-hearted chatter at the beginning, followed by slightly more serious science, followed by a frenzied crescendo of super nerdy ramblings, followed by an abrupt “OMG MY HEAD’S GOING TO EXPLODE!” sentence, followed by me literally collapsing in sleep! lol (Don’t worry, I’ll wake up in a little to watch more Mindy!) Haha :)

In all seriousness though, I hope today’s post was helpful :) The main point is: ADHD and autism are linked to gastrointestinal distress, just like depression and anxiety – and celiac disease/gluten issues are often the key players in instigating that distress. If our gut microbiome is out of whack (because of gluten-fueled inflammation, issues with HPHPA levels or any other variety of reasons), there’s a strong chance our mind will be influenced too, because our gut and brain talk to each other – resulting in a complex relationship known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

Multiple studies have shown that restoring homeostasis to the gut microbiome (which, in the case of celiac disease patients, means implementing a gluten-free diet) can improve psychological problems – including, as discussed today: ADHD and autism spectrum disorder. There’s a lot of controversy surrounding the pathophysiology of each disorder, but one thing seems to be clear: Going gluten-free helps a lot of people – even if we don’t completely understand why! :)

So that pretty much does it for today! If you still can’t get enough gut microbiome research, check out: The Gut Microbiota – Masters of Host Development and Physiology and/or browse through the reference list below (it’s a long one today!). Otherwise, thanks for reading and I’ll talk to you guys (hopefully!) later this week! :)

Thanks so much for stopping by!

xo Jessica ♥

If you learned anything from today’s post, I’d be super grateful if you’d consider sharing with your friends or followers ♥ (Share buttons are way down at the bottom!)

And while we’re talking social media, feel free to join Prayers and Apples on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest! ♥

You can also subscribe to receive notifications about future posts here! :)

References

Addolorato, G., Capristo, E., Ghittoni, G., Valeri, C., Mascianà, R., Ancona, C. & Gasbarrini, G. (2001). Anxiety but not depression decreases in coeliac patients after one-year gluten-free diet: a longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 36(5): 502-6.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Bercik, P., Verdu, E.F., Foster, J.A., Macri, J., Potter, M., Huang, X., Malinowski, P., Jackson, W., Blennerhassett, P., Neufeld, K.A., Lu, J., Khan, W.I., Corthesy-Theulaz, I., Cherbut, C., Bergonzelli, G.E. & Collins, S.M. (2010). Chronic gastrointestinal inflammation induces anxiety-like behavior and alters central nervous system biochemistry in mice. Gastroenterology, 139(6): 2102-2112.

Bercik, P., Park, A.J., Sinclair, D., Khoshdel, A., Lu, J., Huang, X., Deng, Y., Blennerhassett, P.A., Fahnestock, M., Moine, D., Berger, B., Huizinga, J.D., Kunze, W., McLean, P.G., Bergonzelli, G.E., Collins, S.M., Verdu, E.F. (2011). The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication. Neurogastroenterology and Motility: The Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society, 23(12): 1132-9.

Bruce-Keller, A.J., Salbaum, J.M., Luo, M., Blanchard, E., Taylor, C.M., Welsh, D.A. & Berthoud, H-R. (2015). Obese-Type Gut Microbiota Induce Neurobehavioral Changes in the Absence of Obesity. Biological Psychiatry, 77(7): 607–15.

Ciacci, C., Iavarone, A., Mazzacca, G. & De Rosa, A. (1998). Depressive symptoms in adult celiac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 33(3): 247-50.

Del Campo, N., Chamberlain, S.R., Sahakian, B.J. & Robbins, T.W. (2011). The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 69(12): e145-e157.

Donaldson James, S. (September 12, 2013). Anxiety in your head could come from your gut. ABC News. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

Drossman, D.A. (May-June 1998). Presidential address: Gastrointestinal illness and the biopsychosocial model. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60(3): 258-67.

Field, D., Garland, M. & Williams, K. (2003). Correlates of specific childhood feeding problems. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 39(4); 299–304.

Forsythe, P. & Kunze, W.A. (2013). Voices from within: Gut microbes and the CNS. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 70: 55-69.

Fuller-Thomson, E. & Sulman, J. (2006). Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: Findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflammatory Bowel Disease, 12: 697-707.

Genuis, S.J. & Bouchard, T.P. (2010). Celiac disease presenting as autism. Journal of Child Neurology, 25(1): 114-9.

Gill, S.R., Pop, M., DeBoy, R.T., Eckburg, P.B., Turnbaugh, P.J., Samuel, B.S., Gordon, J.I., Relman, D.A., Fraser-Liggett, C.M. & Nelson, K.E. (2006). Metagenomic Analysis of the Human Distal Gut Microbiome. Science, 312(5778): 1355-1359.

Ledford, J.R. (2006). Feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21(3): 153-166.

Mayer, E.A. (2011). Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nature Review of Neuroscience, 12(8): 453-466.

Mulle, J.G., Sharp, W.G. & Cubells, J.F. (2013). The gut microbiome: A new frontier in autism research. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(2): 337.

National Institutes of Health Human Microbiome Consortium. (January 2008). Human Microbiome Project Reference Genomes. Retrieved: May 19, 2015.

Niederhofer, H. (2011). Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and celiac disease: A brief report. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 13(3): PCC.10br01104.

Peters, S.L., Biesiekierski, J.R., Yelland, G.W., Muir, J.G. & Gibson, P.R. (2014). Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non coeliac gluten sensitivity – an exploratory clinical study. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 39(10): 1104-1112.

Sharp, W.G., Jaquess, D.L. & Luckens, C.T. (2013). Multi-method assessment of feeding problems among children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(1): 56-65.

Shaw, W. (2010). Increased urinary excretion of a 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3-hydroxypropionic acid (HPHPA), an abnormal phenylalanine metabolite of Clostridia spp. in the gastrointestinal tract, in urine samples from patients with autism and schizophrenia. Nutritional Neuroscience, 13(3): 135-43.

Sommer, F. & Backhed, F. (2013). The gut microbiota – masters of host development and physiology. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 11(4): 227-38

Sudo, N., Chida, Y., Aiba, Y., Sonoda, J., Oyama, N., Yu, X.N., Kubo, C. & Koga, Y. (2004). Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. The Journal of Physiology, 558(Pt. 1): 263-275.

Whiteley, P., Haracopos, D., Knivsberg, A.M., Reichelt, K.L., Parlar, S., Jacobsen, J., Seim, A., Pedersen, L., Schondel, M. & Shattock, P. (2010). The ScanBrit randomised, controlled, single-blind study of a gluten- and casein-free dietary intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutritional Neuroscience, 13(2): 87-100.

Leave a Reply