Mind you: This is an actual question I posed to my brother on an elevator full of people. You know, during those awkward, radio-silent few minutes when five adults cram into a teeny-tiny space and people occasionally mention the weather or tell you to have a good day? Yep. “So, why aren’t more people talking about tryptophan?” That’s what I came up with.

Consequently, my tryptophan snafu totally cemented my brother’s suspicions that I am, in fact, Sue Heck from The Middle:

(No joke, that is exactly what my brother’s face looks like when I ask questions!)

(No joke, that is exactly what my brother’s face looks like when I ask questions!)

But for real…

Ever since our last post, I haven’t been able to able stop thinking: Given the toxic love triangle we’ve already got going between unhealthy eating, inactivity and depression, why aren’t more people intrigued by the dynamic between serotonin (our little happy chemical) and tryptophan (the main ingredient in serotonin and an essential amino acid that can only be obtained through food)?

Seriously, think about it:

In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that more than one third of U.S. adults are obese; during that same time period, the National Institute of Mental Health found that an estimated 16 million U.S. adults had at least one major depressive episode in the past year. And now we’re talking about a chemical that influences mood that can only be created by eating food?

Either I’m missing something or this is really interesting…

And for now, we’re gonna stick with the latter. (Don’t worry, I googled it: “Latter” means the second one.)

But, surprise! Today’s topic isn’t without a little controversy. Anyone who read last year’s post, Awkward: Your Chemical Imbalance Is Showing, knows that the whole chemical imbalance theory of depression is sorta shot. As Drs. Jeffrey R. Lacasse and Jonathan Leo explain:

Contemporary neuroscience research has failed to confirm any serotonergic lesion in any mental disorder, and has in fact provided significant counter-evidence to the explanation of a simple neurotransmitter deficiency. […] While neuroscience is a rapidly advancing field, to propose that researchers can objectively identify a “chemical imbalance” at the molecular level is not compatible with the extant science. In fact, there is no scientifically established ideal “chemical balance” of serotonin, let alone an identifiable pathological imbalance.

In other words: There’s no proof that depression is caused by a serotonin imbalance. At all. However, serotonin does seem to be mixed up in anxiety and mood disorders somehow – which is why the relationship between tryptophan, serotonin and depression is so interesting.

I say we start by looking at the first two sides of this lil triangular mystery to find some clues…

Time to call in the big guns

(It may be a bad idea to involve Steve from Blue’s Clues in our quest to understand the biosynthesis of 5-hydroxytryptamine, but heck – having a deductive reasoning ninja on our side couldn’t hurt.)

So, if serotonin can only be made with tryptophan, and you have to eat to get tryptophan, and we think serotonin has something to do with depression, then the natural question is: What time did the train leave the station? What happens if you don’t eat?

A 2014 study published in Psychoneuroendocrinology tackled that very question. (On the off chance your issue got lost in the mail, here’s a summary):

Depressive, anxiety and obsessive symptoms frequently co-occur with anorexia nervosa (AN). The relationship between these clinical manifestations and the biological changes caused by starvation is not well understood. It has been hypothesised that reduced availability of tryptophan (TRP) could reduce serotonin activity and thus trigger these comorbid symptoms. The aim of this study, during re-feeding in individuals with AN, was to analyse covariations across measures of nutritional status, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and peripheral serotonin markers.

The findings were just as you might suspect:

Increase in the tryptophan/large neutral amino acid ratio (TRP/LNAA) was correlated with a decrease in depressive symptoms. In addition, there was a positive correlation between serotonin levels and symptoms of both anxiety and depression at discharge. We speculate that enhanced TRP availability during re-feeding, as a result of the increase in the TRP/LNAA ratio, could restore serotonin neurotransmission and lead to a decrease in depressive symptoms.

An earlier article published in Behavioral Pharmacology supports a similar conclusion:

Tryptophan, the precursor of serotonin and an essential amino acid, is only available in the diet. It is therefore likely that excessive diet restriction and malnutrition decrease brain serotonin stores because the precursor is less available to the rate-limiting enzyme of 5-HT [serotonin] biosynthesis… […] It is suggested that tryptophan supplementation may improve pharmacotherapy in anorexia nervosa.

But not so fast…

Research published in the Archives of General Psychiatry looked at 43 untreated depressed patients who underwent tryptophan depletion in a double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. (Try saying that ten times fast.) The result? Patients’ mood did not change when tryptophan was depleted… but did change the day after the depletion test! The study concluded:

That tryptophan depletion did not rapidly worsen depression argues that serotonin function is not linearly related to the level of depression and if reduced serotonin function does cause depression, then it is either as a predisposing factor or due to a postsynaptic deficit in the utilization of serotonin.

Right there with ya, buddy…

So we’re kinda right back where we started. But at least the big-wigs confirmed our suspicions: Altering tryptophan intake does alter mood. Somehow.

In some way.

(That we’re not completely sure of.)

But we know it has something to do with serotonin.

See why I think we should talk about this more?

I know what you’re thinking: OMG! This blog is awesome! How do I subscribe?! Should depression patients start taking tryptophan supplements? The short answer (for now) is: No.

(I know, I wasn’t expecting that one either!)

A 2002 review of 108 tryptophan supplement/depression studies found that only two were legit enough to be mentioned (meaning that the other studies had flaws which, at least according to the review’s authors, discredit their findings). The cool news is that in those two studies, tryptophan treatments proved more efficient than placebos at alleviating depression. However, the point is: right now, clinical evidence is still sparse.

Also, in 1990, tryptophan supplementation was implicated in 1,500 reports of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) and 37 deaths, leading to a product recall. Although about 95% of all EMS cases were traced back to tryptophan produced by a single manufacturer in Japan, suggesting a factory-specific contamination, the tragedy tainted public opinion concerning tryptophan treatment. (After the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, tryptophan was once again made available as a dietary supplement.)

So, for the moment, I’m reserving my thoughts on tryptophan supplementation. However, I don’t see any harm in upping your natural tryptophan intake! :) Again, not quite sure what will happen (also, I’m not a doctor – hence the whole, “who knows if this is a good idea?” thing) but increasing natural tryptophan intake and manipulating how certain foods are consumed (i.e., in what combination/at what time) seems like a potentially fascinating area for study. Looking forward to researching a follow up post ;)

*Just feel like I should stress this one more time:

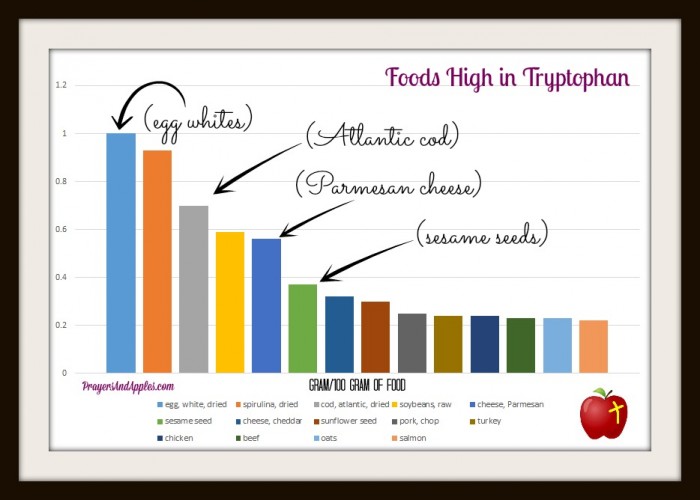

Oh! And here’s a handy dandy chart I whipped up for those of you who stuck around til the end!

Hope today’s post got you thinking!

#SueHeckForPresident

Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (March 28, 2014). Adult Obesity Facts. Retrieved: August 27, 2014.

Delgado, P.L., Price, L.H., Miller, H.L., Salomon, R.M., Aghajanian, G.K., Heninger, G.R. & Charney, D.S. (November 1994). Serotonin and the Neurobiology of Depression: Effects of Tryptophan Depletion in Drug-Free Depressed Patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(11), pp. 865-74. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110025005.

Gauthier, C., Hassler, C., Mattar, L., Launay, J.M., Callebert, J., Steiger, H., Melchior, J.C., Falissard, B., Berthoz, S., Mourier-Soleillant, V., Lang, F., Delorme, M., Pommereau, X., Gerardin, P., Bioulac, S., Bouvard, M., EVHAN Group & Godart, N. (January 2014). Symptoms of depression and anxiety in anorexia nervosa: links with plasma tryptophan and serotonin metabolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 39, pp. 170-8. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.009.

Haleem, D.J. ( September 2012). Serotonin transmission in anorexia nervosa. Behavioral Pharmacology, 23(5-6), pp. 478-95. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328357440d.

National Institute of Mental Health. (nd). Major Depression Among Adults. Retrieved: August 27, 2014.

Ogden, C.L., Carroll, M.D., Kit, B.K. & Flegal, K.M. (2014). Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011-12. Journal of the American Medical Association, 311(8), 806-814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732.

Shaw, K., Turner, J. & Del Mar, C. (August 2002). Are tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan effective treatments for depression? A meta-analysis. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(4), pp. 488-91.

Chart source: United States Department of Agriculture: National Nutrient Database

Leave a Reply