Don’t worry! This is our last antidepressant post for a while (I know it’s been getting pretty heavy up in here)! I just really wanted to share everything that’s gone into the development of my research project so you guys could better understand where I’m coming from ♥

I also wasn’t kidding about needing your help ;) (More on that in a sec!)

So as you probably guessed from today’s cryptic post title…

My research project centers around developing a public awareness campaign countering the chemical imbalance theory of depression! (Surprise!! lol) Kinda similar to the anti-tobacco “Truth” campaign:

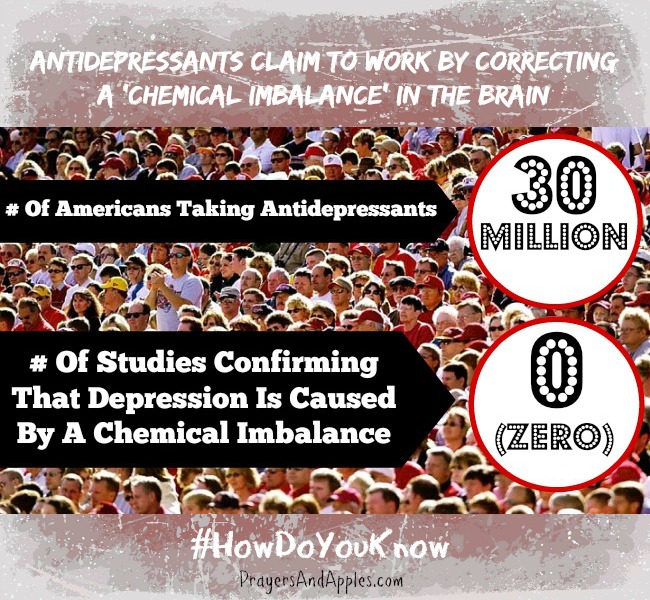

Only our version would look more like this:

While the chemical imbalance/serotonin hypothesis has long since been discredited within scientific circles, the general public has pretty much been left in the dark (thanks to never-ending antidepressant commercials pushing the theory). Addressing this issue, Ronald Pies, Editor in Chief Emeritus of Psychiatric Times, says:

As for professional organizations, I would agree that more could have been done over the years, on the part of the professional leadership, by way of dispelling the “chemical imbalance” slogans of the pharmaceutical industry […]

[P]sychiatry recognizes that alterations in brain chemistry may sometimes be effects, rather than causes, of psychiatric illness; or else signify some deeper, underlying etiology […]

Yes, this kind of holistic message should have come earlier and stronger from psychiatry’s academic and professional leadership. I am sure I could have done more in this regard. But I stand by my claim that no respected representatives of the profession seriously asserted a simple, “chemical imbalance” theory of mental illness in general.

So my goal is to restore balance to the pop culture dialogue :) If medications are going to be marketed directly to patients, then patients – as consumers – deserve to know what’s really going on!

And that’s where you guys come in!

Since my research addresses a lot of public perception issues, I’d love to hear YOUR thoughts. If you wouldn’t mind completing the brief survey below – it’s totally anonymous, I promise!! – I’d really appreciate it! ♥

#HowDoYouKnow Survey

Thank you so, so much! And now, without further ado…

Here’s my official proposal!

Rapid expansion of the antidepressant market has been partially credited to direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) campaigns that claim that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs) effectively treat depression by correcting a “chemical imbalance” caused by a dysregulation of serotonin in the brain (Donohue, Berndt, Rosenthal, Epstein & Frank, 2004; Lacasse & Leo, 2005). However, this theory – known as the “serotonin hypothesis” of depression – not only lacks empirical confirmation (Dubvosky, Davies & Dubvosky, 2003), but has also been increasingly challenged by the academic community (Glenmullen, 2000; Kendler, 2005; Angell, 2011). Given the impassioned objections of numerous leaders within the psychiatric field (see: The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth by Harvard lecturer on medicine, Irving Kirsch), the unprecedented use and influence of DTCA (in 2005, SSRI/SNRI promotional spending exceeded $1 billion, with over $345 million attributed to DTCA; patients are now presenting with self-described “chemical imbalances”) (Donohue, Cevasco & Rosenthal, 2007; Kramer, 2002) and the magnitude of affected individuals (between 1988-1994 and 2005-2008, antidepressant use in the United States increased 400%; one in 10 Americans, aged 12 and over, now takes an antidepressant) (Pratt, Brody & Qiuping, 2011), I propose that research is warranted to:

1) Determine whether a public awareness campaign countering the serotonin hypothesis of depression is appropriate and, if so,

2) Establish specific strategies necessary for successful implementation.

Cultural Context

Antidepressants are being marketed directly to patients via campaigns that present the serotonin hypothesis as a “collective scientific belief” (Lacasse & Leo, 2005) – a profit-driven strategy that has turned this once primarily science-bound controversy into a consumer rights issue of unparalleled significance. If the claims and implications of antidepressant DTCA stand in direct contrast to existent science – if the premise of their suggested efficacy is hypothetical at best – then counter evidence must be highlighted with equal weight so that patients, as consumers, can make better educated purchase decisions. As Harvard Medical School professor Joseph Glenmullen writes, “A serotonin deficiency for depression has not been found” (2000). And yet, sales of drugs marketed to “fix” such a deficiency (see Table 1) continue to rise.

In 2011, Americans spent a record $29.7 billion on antidepressants and antipsychotics (IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, 2013). The most recent IMS review shows that while mental health spending in 2013 registered at $23.8 billion, the field still remains the third highest drug-spending category in the country, second only to oncology and antidiabetes (2014). As established by Donohue et al. (2004), DTCA plays a direct role in spending behavior: In a study of over 30,000 depressed patients between 1997-2000, individuals with depression during periods when class-level antidepressant DTCA spending was highest were shown to have 32% relative odds of initiating medication therapy compared with those diagnosed when DTCA spending was lowest.

The FDA concedes that “reductionist statements” are used by these campaigns “in an attempt to [communicate with] the fraction of the public that functions at no higher than a 6th grade reading level” (Lacasse & Leo, 2005). My proposal aims to utilize a strategically similar approach.

Question Development

I’ve always been perplexed by the notion that pills can fix sadness. After beginning a formal exploration of the subject, my curiosity grew: Surely the tandem, meteoric rise of our nation’s mental health crisis and obesity epidemic couldn’t be a coincidence? Equally intrigued by a cultural shift in morals (could an abandonment of God be to blame for increased feelings of emptiness, anxiety and despair?) – and freshly inspired by Stephanie Peabody & Kurt Fischer’s course, Mind, Brain, Health and Education (2010) – I founded a website focused on mind-body-spirit research: PrayersAndApples.com. This venture led to two startling realizations:

1) There is no conclusive evidence that depression is caused by a “chemical imbalance” – a theory at the basis of almost every patient decision to begin antidepressant medication. (The American Psychiatric Press textbook (2003) reiterates, “Additional experience has not confirmed the monoamine depletion hypothesis”.)And,

2) Despite the fact that numerous leaders within the psychiatric field have rejected the serotonin hypothesis (Elliot Valenstein (1998) writes, “Although it’s often stated with great confidence that depressed people have a serotonin or norepinephrine deficiency, the evidence actually contradicts these claims”), the average consumer has no idea that this premise is even subject to dispute.

Although significant strides have been made in academic, literary and even legislative circles (the Alaska Supreme Court noted in Myers v. Alaska Psychiatric Institute that “psychotropic medication can have profound and lasting negative effects on a patient’s mind and body”), balanced debate within the pop culture forum is still lacking. As a former director of corporate marketing, I began thinking of ways to correct this informational imbalance.

Research Structure

As antidepressant commercials are often showcased between episodes of Keeping up with the Kardashians, I believe a failure to address the claims of psychopharmaceutical propaganda within a pop culture context reflects a refusal to fight the battle where it’s being won. (However, one must first establish that there is, in fact, a battle to be fought.) If approved, my thesis would begin with a historical overview, focused on anticipatory consumer concerns, such as: Where did the “chemical imbalance” theory come from? Why was it initially supported? What has changed to make us question it now? Working towards a resolution of Part One of my research question (“Is a public awareness campaign warranted?”), I plan to review current objections and alternative research trends (i.e., Craft & Perna, 2004; Bonelli, Dew, Koenig, Rosmarin & Vasegh, 2012), before transitioning into a discussion of consumer rights. Having established the validity of my overall critique, I would then conclude with an argument supporting my specific model of proposed change – highlighting the importance of a pop culture platform as well as similar, successful campaigns (see: The American Legacy Foundation, 2015).

The second half of my paper would focus on resolving Part Two of my research question (“What strategies are required for successful implementation?”). Drawing on previous public relations experience, I would build from a detailed analysis of antidepressant DTCA – placing particular emphasis on scenario responses to my proposed counter-campaign. I would conclude with a broad strokes proposal aimed at restoring balance to the pop culture dialogue – my primary concern remaining: that information is relayed responsibly. The dangers of discontinuing medication should be highlighted, as well as deference to expert medical opinion. Just as antidepressant commercials urge patients to, “Ask your doctor about Antidepressant X”, my campaign would, primarily, urge patients to simply ask about something else.

Importance to Field

I feel confident, against the harshest critiques of hyperbole, in saying: Psychology is at a crossroads – and the actions, or inactions, taken by its representatives in addressing the aforementioned antidepressant controversy will drastically influence the future of the entire field.

If the pharmaceutical industry is correct in propagating the serotonin hypothesis, then psychology must contend with its challengers – publicly reconciling the critiques of its own leaders. (As David Healy warns in Anatomy of an Epidemic, “If psychiatry wants to retain its credibility with the public, it will now have to engage with [this] scientific argument”) (Whitaker, 2010). However, if the premise of this proposal is accepted and there is not enough evidence to warrant widespread promotion of the serotonin hypothesis, then psychology must act swiftly, restoring authority and balance to the pop culture dialogue – or risk being bullied out of its own field by DTCA. For if it is found that these medications do not fulfill the cures of their promise – if it is found that other, more effective treatments were neglected in favor of their pursuit, that the side effects of antidepressants hinder well-being or, worse yet: exacerbate disease progression – then society will inevitably turn, not to the pharmaceutical industry, but to psychology and ask: Why didn’t you help us? Why didn’t you tell us what you know?

My research proposal aims not to resolve the scientific intricacies at the core of this debate, but rather to preserve the integrity of the field and safeguard the treatment of patients through a transparent dissemination of knowledge. Speaking from a public relations perspective, psychology’s best hope is to stay one step ahead of this unprecedented controversy.

**Table One**

| TABLE 1 Selected Consumer Advertisements for SSRIs from Print, Television, and the World Wide Web – Lacasse & Leo (2005) | |

| Medication Selected Content from Consumer Advertisement | |

| Citalopram | “Celexa helps to restore the brain’s chemical balance by increasing the supply of a chemical messenger in the brain called serotonin. Although the brain chemistry of depression is not fully understood, there does exist a growing body of evidence to support the view that people with depression have an imbalance of the brain’s neurotransmitters” (1) |

| Escitalopram | “LEXAPRO appears to work by increasing the available supply of serotonin. Here’s how: The naturally occurring chemical serotonin is sent from one nerve cell to the next. The nerve cell picks up the serotonin and sends some of it back to the first nerve cell, similar to a conversation between two people. In people with depression and anxiety, there is an imbalance of serotonin – too much serotonin is reabsorbed by the first nerve cell, so the next cell does not have enough; as in a conversation, one person might do all the talking and the other person does not get to comment, leading to a communication imbalance. LEXAPRO blocks the serotonin from going back into the first nerve cell. This increases the amount of serotonin available for the next nerve cell, like a conversation moderator. The blocking action helps balance the supply of serotonin, and communication returns to normal. In this way, LEXAPRO improves symptoms of depression” (2) |

| Fluoxetine | “When you’re clinically depressed, one thing that can happen is the level of serotonin (a chemical in your body) may drop. So you may have trouble sleeping. Feel unusually sad or irritable. Find it hard to concentrate. Lose your appetite. Lack energy. Or have trouble feeling pleasure… to help bring serotonin levels closer to normal, the medicine doctors now prescribe most often is Prozac” (3) |

| Paroxetine | “Chronic anxiety can be overwhelming. But it can also be overcome… Paxil, the most prescribed medication of its kind for generalized anxiety, works to correct the chemical imbalance believed to cause the disorder” (4) |

| Sertraline | “While the cause is unknown, depression may be related to an imbalance of natural chemicals between nerve cells in the brain. Prescription Zoloft works to correct this imbalance. You just shouldn’t have to feel this way anymore” (5) |

|

REFERENCES 1. Forest Pharmaceuticals. (2005). Frequently asked questions. New York: Forest Pharmaceuticals. Available: http://www.celexa.com/Celexa/faq.aspx. Accessed 17 October 2005. 2. Forest Pharmaceuticals. (2005). How Lexapro (escitalopram) works. New York: Forest Pharmaceuticals. Available: http://www.lexapro.com/english/about_lexapro/how_works.aspx. Accessed 17 October 2005. 3. Eli Lilly. (1998 January). Prozac advertisement. People Magazine: 40. 4. GlaxoSmithKline. (2001 October). Paxil advertisment. Newsweek: 61. 5. Pfizer. (2004 March). Zoloft advertisement. Burbank (California): NBC. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392.t002 |

|

References

American Legacy Foundation. (2015). “Truth” campaign.

Angell, M. (2011 June 23). The epidemic of mental illness: Why? The New York Review of Books.

Bonelli, R., Dew, R.E., Koenig, H.G., Rosmarin, D.H. & Vasegh, S. (2012). Religious and spiritual factors in depression: Review and integration of the research. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012.

Craft, L.L. & Perna F.M. (2004). The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(3), 104-111.

Donohue, J.M., Berndt, E.R., Rosenthal, M., Epstein, A.M. & Frank, R.G. (2004). Effects of pharmaceutical promotion on adherence to the treatment guidelines for depression. Medical Care, 42(12): 1176-85.

Donohue, J.M., Cevasco, B.A. & Rosenthal, M.B. (2007). A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. New England Journal of Medicine, 357: 673-681.

Dubvosky, S., Davies, R., Dubvosky, A. (2003). Mood disorders. In R. Hales & S. Yudofsky (Eds.), The American psychiatric textbook of clinical psychiatry (4th ed.), (pp. 439-542). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Glenmullen, J. (2001). Prozac backlash: Overcoming the dangers of prozac, zoloft, paxil and other antidepressants with safe, effective alternatives (p. 384). New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. (May 2013). Declining medicine use and costs: For better or worse? A review of the use of medicines in the United States in 2012.

IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. (April 2014). Medicine use and shifting costs of healthcare: A review of the use of medicines in the United States in 2013.

Kendler, K.S. (2005). Toward a philosophical structure for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162: 433-440.

Kirsch, I. (2010). The emperor’s new drugs: Exploding the antidepressant myth. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Kramer, T.A.M. (2002). Endogenous versus exogenous: Still not the issue. Medscape General Medicine, 4(1).

Lacasse, J.R. & Leo, J. (2005). Serotonin and depression: A disconnect between the advertisements and the scientific literature. PLoS Medicine, 2(12): e392.

Myers v. Alaska Psychiatric Institute, Alaska Supreme Court No. S-11021.

Pratt, L.A., Brody, D.J. & Qiuping, Gu. (2011). Antidepressant use in persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2005-2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NCHS Data Brief, No. 76.

Valenstein, E.S. (1998). Blaming the brain: The truth about drugs and mental health (p. 292). New York: Free Press.

Whitaker, R. (2010). Anatomy of an epidemic: Magic bullets, psychiatric drugs, and the astonishing rise of mental illness in America. New York, New York: Broadway Books.

RELATED POSTS

The Strange Start of Psychopharmacology (Part One)

A Funny Little Story About Rocket Fuel (Part Two)

Where Did the “Chemical Imbalance” Theory Come From? (Part Three)

Awkward: Your Chemical Imbalance is Showing

Mind blown. This is amazing!!!!!! You are going to change the world of pharmaceutical drugs!

Thank you so much! I’m so humbled my all of the positive feedback I’ve gotten today! The survey results have been fascinating – can’t wait to share as this project progresses! Thanks again! xo