If you follow Prayers and Apples on Facebook, you know today’s post kicks off #HowDoYouKnow week (wahoo!) – which basically means I get to spend the next five days trying to convince you guys to help me with my final research project ;)

Mission number one? Review Robert Whitaker‘s

Mission number one? Review Robert Whitaker‘s masterpiece book, Anatomy of an Epidemic!

(If you follow Prayers and Apples on Facebook – or Instagram! – you’ll also notice that #OperationPalmTrees was a success ;) Yay for lil umbrellas in my drinks!)

(If you follow Prayers and Apples on Facebook – or Instagram! – you’ll also notice that #OperationPalmTrees was a success ;) Yay for lil umbrellas in my drinks!)  Not on social media? No worries! :) #HowDoYouKnow is a hashtag I created to go along with my research project – which basically aims to counter the serotonin hypothesis of depression in a pop culture context. (That sounded way more complicated than it is!) Basically: Antidepressant commercials are always suggesting that depression is caused by a “chemical imbalance” – but there’s no real proof to back that up. More and more big name scientists are stepping up to say it’s not true – but the message isn’t making it to mainstream media near as much as it needs to. My project aims to spread the word through normal, every day outlets like commercials, social media and magazines. (#HowDoYouKnow refers to the idea that a doctor can just look at you and tell that you have a “chemical imbalance”. Really? How do you know?)

Not on social media? No worries! :) #HowDoYouKnow is a hashtag I created to go along with my research project – which basically aims to counter the serotonin hypothesis of depression in a pop culture context. (That sounded way more complicated than it is!) Basically: Antidepressant commercials are always suggesting that depression is caused by a “chemical imbalance” – but there’s no real proof to back that up. More and more big name scientists are stepping up to say it’s not true – but the message isn’t making it to mainstream media near as much as it needs to. My project aims to spread the word through normal, every day outlets like commercials, social media and magazines. (#HowDoYouKnow refers to the idea that a doctor can just look at you and tell that you have a “chemical imbalance”. Really? How do you know?)

Enter: Pulitzer Prize finalist and George Polk Award for Medical Writing winner, Robert Whitaker, and his AMAZING book, Anatomy of an Epidemic!

I don’t wanna go to jail, but I feel like that might happen…

So before I share my formal research proposal on Friday’s blog, I wanted to give you guys plenty of background (because I wasn’t kidding about needing your help!). Anatomy of an Epidemic is the perfect segway for Friday’s post, because Whitaker does an incredible job of summarizing the history of different drugs – so incredible, in fact, that I couldn’t help but engage in some serious paraphrasing action. (Is it still plagiarizing if you encourage everyone to go buy the book? Seriously, check out Amazon – used copies starting at just $5!)  For real though: I’m going to be sharing bits and pieces of Whitaker’s work over the next few days, but you guys seriously need to pick up a copy! Hands down, the most influential book I’ve ever read!

For real though: I’m going to be sharing bits and pieces of Whitaker’s work over the next few days, but you guys seriously need to pick up a copy! Hands down, the most influential book I’ve ever read!

Ok, with that said, here we go! This next part’s paraphrased from Chapter 4: Psychiatry’s Magic Bullets…

The drug that started it all

Back in the 1940s, researchers were testing a group of drugs called “phenothiazines”. In 1946 they found out that one of them, “promethazine”, had antihistaminic properties – which meant that it might be useful in surgery. (Our bodies release histamine in response to wounds and other conditions; if the response is too strong, it can lead to a drop in blood pressure which could prove fatal for surgery patients.) In 1949, a French doctor, Henri Laborit, gave promethazine to several patients and found that, in addition to its antihistaminic properties, the drug induced a “euphoric quietude… patients are calm and somnolent, with a relaxed and detached expression.”

Laborit immediately got excited about the idea of using promethazine as an anesthetic. At the time, barbiturates and morphine were the go-to painkillers/sedatives – but those drugs suppressed overall brain function, making them super dangerous. Promethazine, on the other hand, only acted on selective regions of the brain – making it much safer. If the drug was used as part of a surgical cocktail, Laborit reasoned, it might be possible to use much lower doses of the more dangerous anesthetic agents.

Chemists got to work testing new compounds. They soon found a winner with chlorpromazine: When injected into rats who had been trained to climb a rope whenever they heard a bell (or risk being electrocuted by the floor), chlorpromazine made the rats not only “physically unable” to climb the rope, but also emotionally disinterested in doing so.

The drug seemed perfect for surgery…

Laborit began using chlorpromazine as part of a surgical drug cocktail in 1951. As expected, it put patients into a “twilight state.” Other surgeons tested it as well, reporting that it induced an “artificial hibernation.”

Now here comes the strange part…

In December of that year, Laborit made an observation that suggested that chlorpromazine might be of use in psychiatry, noting that it “produced a veritable medicinal lobotomy.” (Now, keep in mind: A lobotomy involves severing connections in your brain’s prefrontal cortex – seen as a controversial treatment back in the day but, um, basically a mutilating surgery in hindsight. So not exactly a good thing either way…)

In December of that year, Laborit made an observation that suggested that chlorpromazine might be of use in psychiatry, noting that it “produced a veritable medicinal lobotomy.” (Now, keep in mind: A lobotomy involves severing connections in your brain’s prefrontal cortex – seen as a controversial treatment back in the day but, um, basically a mutilating surgery in hindsight. So not exactly a good thing either way…)

One year later, two prominent French psychiatrists, Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker, began administering chlorpromazine to psychotic patients at St. Anne’s Hospital in Paris…

(I know – it’s like that part in the movie where you start screaming, “No! No!” at the screen!)

However, at least physicians at the time were aware that the drug wasn’t fixing any known pathology.

“We have to remember that we are not treating diseases with this drug,” said psychiatrist E.H. Parsons, “We are using a neuropharmacologic agent to produce a specific effect.”

And yet…

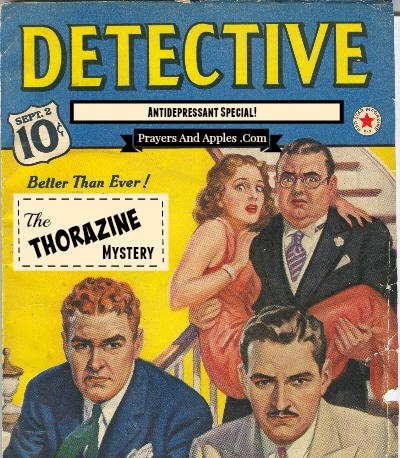

In 1954, chlorpromazine (under the new name, Thorazine) entered the U.S market – publicly promoted as the first “miracle” treatment for mental disease!! – ushering in, as magazines at the time called it: “A new era of psychiatry”.

Hashtag confused face, right?!

AND, as if all that wasn’t disturbing enough: The “chemical imbalance” theory of mental disorders wasn’t introduced until roughly ten years later.

The drugs came first.

Then the theory.

(I think Kate speaks for us all…)

So yeah, we’ve kinda got a lot to talk about

Ok, so this is just the tiniest tip of the iceberg – but stuff like this plays a major role in my research project, so I’d love to hear your thoughts and questions!! (Apologies in advance for not including my normal list of references – I’m still getting settled in down here and trying to blog really fast! – but definitely let me know if you’re interested in any particular point and I’ll get you the citation ASAP!)

All of this information is provided with the hope that you’ll be encouraged to ask your doctor #HowDoYouKnow next time he/she suggests that you, or a family member or friend, suffers from a “chemical imbalance” :) Besides the fact that the theory is unproven (and, judging from that lil history lesson up there: built on some pretty shaky ground), I can’t be the only person who thinks it’s strange that someone could just look at you and see what your chemicals are doing inside your brain ;)

Looking forward to sharing more all this week!

Thanks for reading! And be sure to stop back tomorrow!

xo Jessica

Related Posts:

I really enjoyed this post. How crazy. Love the way you write, it’s so easy to digest. Thanks for this.

Thanks girl! And I know, crazy right?!

Hi Jess! Love reading your stuff! As a Pharmacist, I did have some questions for you. Hopefully to maybe help you out. :) Is your project more geared toward antipsychotics or antidepressants? I know you talk about about chlorpromazine(an atypical antipsychotic) and also mention depression (which utilize other classes of meds). Also, in reference to your statement about drs looking at you and determining you have a chemical imbalance… Is this statement based on the fact that no objective lab/brain test exist in diagnosing psychosis and depression?

Hi Nikki! Yay, so good to hear from you! So my project’s going to be focused solely on antidepressants – the chlorpromazine background is just provided to kinda set the stage for how all the “chemical imbalance” talk got started. I just posted a new article today, Where Did the “Chemical Imbalance” Theory Come From?, that ties the two ideas together :) Chlorpromazine’s widely credited with kicking the whole thing off, so it’s helpful to kinda review and discuss in a historical context, but my project’s going to be just antidepressants. The conversation shifts over to iproniazid in the next post and then goes from there :)

And the doctors looking at you part: Yes, 100% :) (And thanks for pointing that out!) Even IF depression was caused by a dysregulation of serotonin in the brain, it’s humanly impossible to physically sit across from a patient and see how his/her neurotransmitters are behaving. That being said, as Elliot Valenstein explains: “Although it’s often stated with great confidence that depressed people have a serotonin or norepinephrine deficiency, the evidence actually contradicts these claims”. The American Psychiatric Press textbook confirms Valenstein’s observation (“Additional experience has not confirmed the monoamine depletion hypothesis”), as does Essential Psychopharmacology: “There is no clear and convincing evidence that monoamine deficiency accounts for depression; that is, there is no ‘real’ monoamine deficit”). Ronald Pies, Editor in Chief of Psychiatric Times, pretty much sums it up: “In truth, the ‘chemical imbalance’ notion was always a kind of urban legend – never a theory seriously propounded by well-informed psychiatrists”.

(Sorry to bombard your answer w/so many citations! LOL I just wanted to make sure anyone who browsed the comment section had access to plenty of info from today’s new post!) :)

So good to hear from you – and thanks for reading!! Lmk if you have any more questions! xo ♥

Check out wwwrxisk.com

a website that has lots of info about antidepressants …good work Jessica

Louisa

Thanks so much, Louisa! And WOW, what a great resource – thanks so much for sharing!!