Hey guys! Thanks for stopping back! :)

For those of you who missed it, yesterday kicked off a week of posts focused on the “chemical imbalance” theory of depression. (Cliff’s Notes version for new readers: I’m not exactly a huge fan!) I plan on posting a big research proposal I’m working on for school on Friday, so I guess you could say I turned my homework assignment into a week-long theme party!

*Yes, I’ve used that picture before… but somehow it always seems so appropriate lol :)

Oh! And I’ve also created a hashtag for my project (#HowDoYouKnow) – which you could also say is totally nerdy normal.

Alex Dunphy for President. That’s all I’m sayin :)

Quick recap

Ok, so yesterday we talked about Thorazine – a nifty lil anesthetic compound that surgeons found induced “twilight states” and sent patients into “artificial hibernation” – which would be a pretty boring story, except in 1954 Thorazine was… (plot twist!) marketed to the public as a “miracle” treatment for mental disorders!

Anesthetic/Antipsychotic: Tomato/Tomatoe, right?

Haha :) Sorry, I’ve been wanting to use that pic forever! lol :)

So today we’re going to pick up where Thorazine left off – starting with some pretty important questions, like:

What made people think pills could cure mental illness to begin with?

*As with yesterday’s article, today’s post is going to draw heavily on Robert Whitaker’s award-winning book, Anatomy of an Epidemic (partly because his work is genius; partly because I’m super busy with my new move to Florida!). So if you like what you read, head on over to Amazon and pick up a copy (it’s seriously one of my favorite books EVER)!

Now onto the good stuff :)

Even though Thorazine is credited with kicking off the psychopharmaceutical craze, the idea that diseases could be cured with “magic bullets” (a.k.a. pills) actually goes back a little to 1909. After hypothesizing that creating the right drug might allow doctors to kill off bad, disease-causing microbes without hurting the rest of the body, German scientist Paul Ehrlich struck gold with salvarsan – a chemical compound that effectively eradicated the syphilis microbe from rabbits without hurting the rabbits at all.

Ehrlich’s discovery was a sensation (“This was the magic bullet!” Paul de Kruif wrote in 1926. “[It produced] healing that could only be called biblical!”). Scientists immediately scrambled to find the next miracle drug. Before long, the Bayer chemical company introduced the next big thing: a drug capable of treating staph and strep infections. The medical community, and public, were buzzing. By the time penicillin was mass-produced in the early 1940’s, “magic bullets” were all the rage. U.S. Secretary of State, George Marshall, even gave a speech in 1948 predicting that infectious diseases might soon be wiped clear from the face of the earth. A few years later, President Eisenhower did one better: Calling for the “unconditional surrender” of all microbes.

Yep, it was an exciting time in medicine and the United States was pumped. Prior to World War II, most scientific research was funded privately (think: Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller), but after the magic bullet craze, federal funding started pouring in. As Whitaker writes, “the nation looked around for a medical field that had lagged behind… Psychiatry, it seemed, was a discipline that could use a little help.”

Now here’s the part where I remind you that scientists developed psychotropic drugs first, then came up with the “chemical imbalance” theory…

Ok, so I think we all see where this is going: Everyone was expecting big things from drugs (there were “miracles” happening left and right in the medical field) and psychiatry was in a bit of a funk. The state mental institutions were overflowing with patients, which they couldn’t afford, and psychiatrists needed a way to get these people back on the streets. Not to mention, everyone was feeling pressure to turn psychiatry into a “real” medical science.

And what was the hallmark of medical science at the time?

Drugs.

(You don’t need to be a psychic to guess what happened next…)

Lo and behold, Thorazine was introduced in 1954 (right on trend with the magic bullet craze) and psychiatry had its first “miracle” pill. Nevermind that it was actually developed as part of a pharmaceutical cocktail to sedate patients during surgery (#details). As Time magazine wrote in 1955, Thorazine ushered in “a new era of psychiatry”.

You can say that again.

Wait, what about the rocket fuel?

So no joke, this next part’s CRAZY.

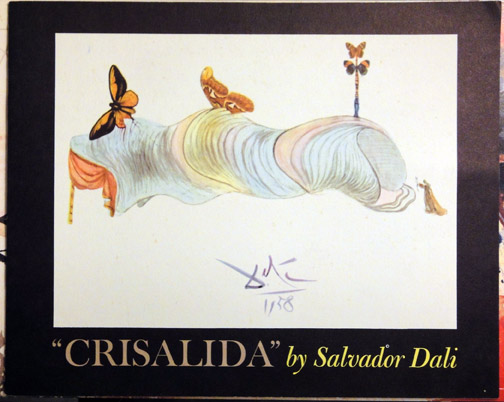

Ok, so first you had Thorazine, which was marketed as a “major tranquilizer”. Then came Miltown – which was sold as a “minor tranquilizer” – and was even more popular than Thorazine. (People LOVED this stuff. Drugstores literally put up signs saying, “YES! WE HAVE MILTOWN!” The laboratories that made it could barely keep up with demand.) Wallace Laboratories even hired famed artist, Salvador Dali, to create an exhibit promoting Miltown:

For real! That’s a picture of the caterpillar-like exhibit people would walk through! It was all dark and claustrophobic, then when you got to the end everything opened up and looked pretty – which was supposed to mimic the experience of taking Miltown. (Doesn’t exactly ring of scientific integrity, does it?)

By the time Librium hit the shelves, the public was sold – hook, line and sinker. Unlike Thorazine and Miltown, Librium was marketed as a mood stabilizer/antidepressant – and the crowd went WILD. But the craziest part? Librium was originally derived from rocket fuel.

Yep, scientists didn’t sit around studying the brains of depressed patients, hypothesizing about causes and then developing treatments. They accidentally stumbled across a cool chemical compound while analyzing rocket fuel and that became the first antidepressant.

Ok, so here’s how it went down:

Towards the end of World War II, when Germany ran low on the liquid oxygen and ethanol used to propel its rockets, it would use a chemical compound called hydrazine. Well after the war, chemical companies from Allied countries scooped up all the hydrazine to see if there was anything they could do with it. In 1951, chemists at Hoffmann-La Roche created two hydrazine compounds (isoniazid and iproniazid) that seemed to be good at fighting tuberculosis. Cool side-effect? The drugs seemed to “energize” patients.

Now, I’m going to give you one guess what the generic name for Librium was. (Hint: It wasn’t isoniazid.)

Yep, you guessed it: Iproniazid.

Mind = Blown.

Now look, it’s not like we’re all walking around ingesting rocket fuel – but the point is: Drugs to treat depression were created before the whole “chemical imbalance” theory of depression was even formed. The fact that scientists stumbled upon them in such accidental, random ways makes the whole thing, well, even more disturbing :/

Stay tuned tomorrow! Same place, same time!

Like I said, the majority of today’s post was paraphrased from Robert Whitaker’s AMAZING book, Anatomy of an Epidemic – and I can’t encourage you enough to go pick up a copy!

I’m looking forward to tomorrow’s post (whew! if I make my goal of posting every day this week, it’ll be a world record!) and I can’t wait to share my full research proposal with you guys on Friday! (Don’t forget, I’m going to need your help!) :)

And remember: All of this information is provided with the hope that you’ll be encouraged to ask your doctor #HowDoYouKnow next time he/she suggests that you, or a family member or friend, suffers from a “chemical imbalance”. Besides the fact that the chemical imbalance theory is unproven (and, just based on that lil history lesson above: built on some pretty shaky ground!), I can’t be the only person who thinks it’s strange that someone can just look at you and see what your chemicals are doing inside your brain ;)

Thanks so much for reading!

Talk to you guys tomorrow!

xo Jessica

Related Posts:

The Strange Start of Psychopharmacology (Part One)

Great article. I like that you pointed out the HowDoYouKnow question that people should be asking their doctors before they start taking pills. Doctors don’t know if you have a chemical imbalance, that is for sure. But, they do know with trial and error that if a medicine is making you feel much better then it is working. I would suggest if people to decide to go down the path of taking medications, to take the genetic test from http://www.genomind.com to see what class of medications and vitamins work well with your genetics.

Thanks girl – and great point! One of the reasons all these drugs have become so popular is that people *do* feel better on them (hence the reason ppl were lining up around the block for Miltown!). But more and more studies are showing the comparative (and often: superior!) benefits of other treatments, which don’t have all the nasty side effects (such as exercise, spiritual involvement, improved nutrition – lots of cool gut microbiome research in that area!). Hopefully through this project we can draw more attention to those alternatives, because at the end of the day: Depression is real and it needs a REAL treatment :) Just maybe not a pill ;)

Thanks so much for reading, commenting and always being so supportive! xo HUGS ♥

You are so right. I’m all for alternative treatments. I think this blog will really make people think twice about starting with medication. There is hope, and your articles are giving people hope. Great work!

Thank you!! I hope so!! ♥

I remember the ‘Chemical Imbalance’ craze, it was pretty rampant wasn’t it.This was great to read Jessica, thank you for giving us some hard evidence and history surrounding its creation. I despise being lied to on such a grand scale by corporations, industry and even governments. It just seems to be everywhere and its great that we are all becoming better informed through websites like yours. Should we be really be so surprised though? Tobacco Industry … Jeffrey Wigand, George Bush , Monsanto etc etc. Great work Jess X