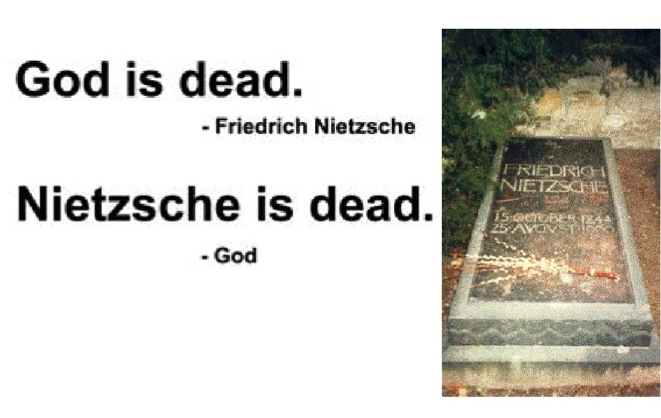

My philosophy class has been focusing a lot on the origins of human rights (basically: we all think we should have them, we just disagree on why). There’s a couple different schools of thought. John Locke has this whole social contract theory, usually referred to as ‘Natural Law.’ Basically, he says we’re all equal because we’re all made in the image of God. Therefore, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander. (I’ve been looking for an excuse to use that expression forever!) Not surprisingly, people who don’t believe in God think Locke’s premise is a little problematic. But even atheists agree that morality gets pretty murky without religion. Take philosopher and atheist Friedrich Nietzsche, who famously wrote in his parable of the madman, “God is dead.” (I think my favorite part of this whole semester was when my professor introduced Nietzsche’s parable and then put this picture on the board):

Even Nietzsche knew it was hard to hold the whole puzzle together without God (that’s actually, partially, what his parable is about). Without God, without a religious foundation, you end up with a lot of why’s – and not a lot of meaning. If we’re not equal because we’re all made in God’s image, then why are we equal? Are we even equal at all? And why should any of us care about about anyone else? If we claim we have human rights, where do they come from?

We talk a lot about spirituality at Prayers and Apples, so I thought we’d take a bit of a philosophy detour today and look at how religion and spiritual beliefs factor into the most fundamental aspects of our being – in this case, human rights. The essay below talks about the work of Michael Perry and Ronald Dworkin. Perry argues that we’re all ‘sacred’ – and that’s our basis for human rights (not too far off from Locke). Dworkin says: Ok cool, I’m down with your sacred thing. But I don’t think the idea of ‘sacredness’ is necessarily a religious idea. And then from there, Perry pretty much says: You’re wrong, and I’m still right. (They use bigger words, but that’s basically the gist.)

If you have time, read on through and let me know your thoughts. (Sorry in advance for the quick wrap-up at the end – we were supposed to just restructure the arguments, but I felt like using the last paragraph of my word limit to toss in my own two cents!)

Can There Be Human Rights Without God?

A Review of Michael Perry’s Claim

Michael Perry argues that the idea of human rights is ineliminably religious. He makes this claim based on the presupposition that the idea of human rights that informs various international human rights doctrines relies, at least in part, on the concept of ‘sacredness’ – that recognition of human rights rests heavily on the notion that “there is something about each and every human being, simply as a human being, such that certain choices should be made and certain other choices rejected…” (p. 208). That something, according to Perry, is ‘sacredness’; a concept that is, again as Perry claims: ineliminably religious. The argument then follows, that if the basis of human rights finds its foothold in the divine sacredness of the individual, and if such sacredness is, in fact, ineliminably religious, then the idea of human rights is, therefore, ineliminably religious as well.

Perry derives his conviction “that every human being is sacred” as a response to the question: What is it about us, as human beings, that requires that “certain things ought not to be done to us and certain other things ought to be done for us?” (pp. 207-208). Perry’s solution (that we are all sacred) appears satisfactory, as the most prominent of human rights doctrines have all alluded to the same concept (be it through phrasing of “inherent dignity”, the individual being “inviolable”, “an end in himself” and so on) (p. 209). Where Perry’s argument diverges, and most criticism begins, is at the assertion that sacredness is inescapably religious.

However, before approaching this claim, let us first return to the presupposition that human rights rely on the notion that human beings are sacred. While this claim may seem unproblematic, Perry outlines two divergent schools of thought which merit review: the Definitional Strategy and the Self-Regarding Strategy. The Definitional Strategy argues for a “moral point of view” – that certain things ought to be done and not done because “we all agree [to look at things morally] in some sense or other, impartially, granting every person some sort of equal status” (p. 241). Perry quickly dismisses this strategy, as it fails to answer David Tracy’s ‘limit-question’: “Why be moral at all?” (p. 242). Turning to the Self-Regarding Strategy, Perry reviews the claim that human rights need not depend on human sacredness to gain meaning; instead, it is enough to know that “it is good for oneself or for one’s family/tribe/nation/race/religion that certain things not be done for every human being” (p. 246). Again, Perry dismisses this approach, claiming that 1) it is unclear how much of a treaty such a concept could support if both or either parties didn’t live in constant fear of one another (in other words, the strategy is little more than a “nonaggression treaty”), and 2) it is unclear how such a strategy could be made to apply to every human being.

Having settled the argument that human rights must therefore be rooted in the notion of the sacred, Perry then prepares his argument for an ineliminably religious definition of the sacred by considering the role of the word ‘religious’ itself. Linking religion to the meaning of life – “a cry for ultimate relationship, ultimate belonging” as Abraham Heschel writes – Perry offers the following definition: a religious vision is “a set of beliefs about how one is or can be bound or connected to the world – to the ‘other’ and to ‘nature’ – and, above all, to Ultimate Reality” (pp. 211, 212). To Perry, then, to call something “religious” is to refer to its core belief that the world is meaningful and that we, as human beings, exist in relationship to both the world and each other. The idea of a religious concept of sacredness would therefore require reliance on these core tenets; any attempt at a non-religious conception of the sacred would need to abandon the notion of a meaningful world with bound relationships to “the Other” and “nature” (p. 212).

Before attempting to discredit any such notion (that there can be an intelligible secular version of sacredness), Perry turns his attention to the non-secular reasoning that, he believes, secures relationships between the self, other and nature. Referencing David Tracy’s idea of “the analogical imagination”, Perry claims that “the Other (the outsider, the stranger, the alien), too, no less than oneself and the members of one’s family or of one’s tribe or nation or race or religion, is a ‘child’ of God”; therefore, God should be imagined as “parent” and fellow human beings as “sister” and “brother” (pp. 216-217). This, Perry claims, is the divine origin of our sacredness – as well as the foundation on which such claims as human rights and equality may find their footing.

The religious conception now defined, Perry seeks out an intelligible secular version to oppose it. Bearing in mind that such a version would have to abandon the notion of a meaningful world and the balance formed by our relationships within it (as prescribed by the definitions above), Perry is left with an argument of secular morality – one he quickly questions: “But is it plausible to think that morality can be independent of any cosmological convictions – any convictions about how the world (including we-in-the-world) hangs together?” (p. 230). Relying heavily on Nietzsche (who wrote: “Naiveté: as if morality could survive when the God who sanctions it is missing!”), Perry discredits this attempt at a secular version of sacredness, claiming there is no place for the concept “to gain a foothold” (p. 232).

However, Ronald Dworkin objects, claiming that “for some of us, [the sacredness of human life] is a matter of religious faith; for others, of secular but deep philosophical belief” (p. 232). Dworkin explains that a non-religious view of the sacred is possible if life is viewed as the highest product of creation; if each life is seen as a representing the joined efforts of civilization – if, together, these two ways of thinking inspire and generate awe within us. Then, Dworkin argues, a secular notion of the sacred is possible, because it can be understood as having both intrinsic and objective value. We are sacred because of all of the evolutionary and social efforts that have gone into our creation; we are sacred regardless of whether we recognize our sacredness or not (Mathias, 2013).

Again, Perry is quick to dismiss his counterpart, claiming that Dworkin’s premise seems “less a conviction about (a part of) the world than a kind of free-floating aesthetic preference” (p. 233). Finding that Dworkin’s approach leaves too much definitional wiggle-room (I may arbitrarily decide something inspires awe in me, with which you might completely disagree – where then would be the bond that ties together our agreement on what’s ‘sacred’?), Perry takes greatest issue with what he feels is Dworkin’s subjective use of the word ‘sacred.’ To use the term in its objective sense, Perry suggests, (i.e., “something is sacred and therefore it inspires awe in us”) is to torpedo Dworkin’s claim. As Perry explains, “How do we get from ‘the universe is (or might be) nothing but a cosmic process bereft of ultimate meaning’ to ‘every human being is nonetheless sacred (in the strong objective sense)’?”

Perry claims that we don’t. And, in refuting Dworkin’s secular claim regarding sacredness, Perry concludes with a reiteration of his own thesis: “If – if – the conviction that every human being is sacred is inescapably religious, it follows that the idea of human rights is ineliminably religious, because the conviction is an essential, even foundational, constituent of the idea” (p. 227). Finding that Dworkin did not provide satisfactory evidence that a non-religious version of the sacred exists, Perry determines that it doesn’t – arguing that the idea of human rights is, therefore, inescapably religious.

I agree with Perry, that if the notion of sacredness is found to be inescapably religious then, so too, follows human rights. I believe Perry was correct in dismissing the Definitional and Self-Regarding Strategies, and therefore feel on solid ground saying that human rights are informed by a notion of human sacredness. However, I feel Perry was too quick to dismiss Dworkin. I believe any weakness of Perry’s argument lies in his failure to seriously address Dworkin’s claim that sacredness can be derived from the evolutionary and social elements that shape each individual. Therefore, I do not find his conclusion definitively convincing.

References

Mathias, R. (2013, February 13). Lecture 6: Human Rights: A Philosophical Introduction. Lecture given in GOVT E-1040, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Perry, M.J. (1996). Is the Idea of Human Rights Ineliminably Religious? In A. Sarat & T.R. Kearns (Eds.), Legal Rights: Historical and Philosophical Perspectives (pp. 205-262). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Do you think it’s possible to argue for human rights without religion?

In other words, if we want to demand people behave towards each other in a certain way and/or claim that we’re all equal, what is our foundation for that thought, if God (not necessarily a Christian god, just any head of a spiritual belief) is not thrown in with the mix?

Or do you think that morality is inescapably tied up with religion?

Leave a Reply